Every now and then, evolution produces something so strange it feels like nature fell asleep at the drawing board and a toddler doodled in the margins. The gulper eel is one such masterpiece of madness. It’s a creature that looks like a shoelace, a horror prop, and a carnival gag all at once. It’s long, thin, floppy, and ends in a mouth so absurdly oversized it could swallow prey larger than itself. Imagine a fish designed by committee: one person voted for snake, one for pelican, and someone in the back shouted “balloon animal.” They all won, and the result was the gulper eel.

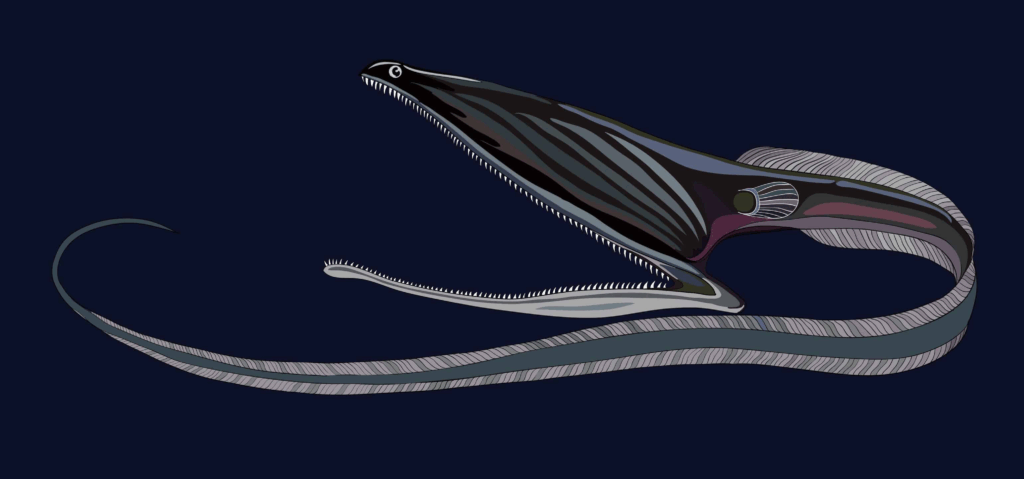

Stretching up to two and a half metres long, the gulper eel is mostly tail. A ridiculously skinny, whiplike tail that wiggles behind it like the string of a kite. Its body is thin, soft, and gelatinous, designed for drifting in the abyssal depths rather than sprinting like a tuna or shark. At first glance, it looks fragile, even pathetic. And then you see the mouth. The jaw unhinges, opens wide, and suddenly you’re staring into a void that looks like it could swallow your hopes and dreams. Its mouth can balloon so massively that it dwarfs the eel’s own body, creating a grotesque pouch like a living net. This is not a predator that carefully chases down its prey. This is a predator that floats, waits, and then turns its entire head into a death trap.

The gulper eel’s most famous party trick is exactly that: swallowing things larger than itself. Shrimp, squid, fish—it doesn’t matter. If it drifts too close, the gulper eel simply scoops it up like a mobile pelican basket. The elasticity of its jaw and stomach means it can expand like a grotesque balloon to fit the catch. Scientists have even found gulper eels with stomachs swollen to ridiculous proportions, like a snake that just swallowed a basketball. It’s both horrifying and funny: imagine bumping into a shoelace with a frog balloon tied to one end. That’s essentially the gulper eel’s aesthetic.

And if the mouth wasn’t absurd enough, the tail adds another twist. Many gulper eels end their tail with a glowing pink or red lure, tipped with bioluminescent organs that can flash in the darkness. This is nature’s equivalent of fishing with a glow stick. While drifting in the abyssal blackness, the eel flickers its tail like a living neon sign. Curious prey wanders close, hypnotised by the glow, and then—wham—the giant mouth snaps shut and another victim disappears into the dark. It’s a sinister twist on carnival games: come for the lights, stay because you’re now inside a balloon animal of doom.

But as much as the gulper eel feels like a bad special effect, it’s very real, and it lives in the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean, usually between 500 and 3,000 metres down. This is the midnight zone, where sunlight doesn’t reach, and life survives in bizarre, energy-saving forms. Here, slow-motion predators thrive. There are no high-speed chases, no elegant tuna dashes, no dramatic shark lunges. There’s just drifting, glowing, and waiting. The gulper eel’s oversized mouth is the perfect adaptation for such a world. When prey is scarce, you can’t afford to be picky—you grab whatever comes your way, however big or small.

Of course, this has led to all sorts of misconceptions about the gulper eel. People often assume it’s related to regular eels like the moray. It isn’t. In fact, it belongs to its own family, the Eurypharyngidae, which roughly translates to “wide throat,” because scientists apparently wanted to keep it literal. Others assume it must be a top predator of the deep. Also wrong. Despite its horrifying mouth, the gulper eel is actually fairly fragile, with a body more like jelly than armour. It’s not here to brawl with sharks—it’s here to vacuum up whatever fits in its ridiculous mouth. And then there’s the assumption that it’s rare. The truth? We don’t really know. Gulper eels are hard to study because they live so deep, but they’re not considered endangered. They may be quietly thriving down there, ballooning their way through the abyss, unseen by human eyes except for the occasional deep-sea camera.

The most unsettling thing about the gulper eel is how alien it looks in motion. Video footage of one swimming shows a long, skinny thread suddenly blooming into a grotesque head, jaws yawning open until it resembles a floating bedsheet ghost. Sometimes it balloons just to intimidate, flaring its jaw like a nightmare parachute even if no prey is present. Picture that drifting silently toward you in the dark, with a glowing red light pulsing at the tip of its tail. Suddenly, sharks don’t seem so bad.

And yet, bizarrely, the gulper eel also has a comedic edge. Its cartoonishly oversized mouth makes it look like a Looney Tunes gag come to life. There’s something inherently funny about a creature that’s basically 90% string with a party balloon at the end. This is the sort of thing you’d sketch as a joke in biology class—“haha, what if a fish had a head way bigger than its body?”—only for evolution to say, “yes, that works.” The gulper eel blurs the line between terrifying and ridiculous, which is precisely why it’s so captivating.

And yes, this is another nail in the coffin for people who insist “but you don’t see that in nature.” Nature is not neat. It is not binary. It is not polite. It’s a shoelace with a balloon head and a glow-stick butt, drifting in the abyss for millions of years because somehow, that design works. If the gulper eel can thrive looking like it escaped from a carnival gone wrong, then anyone arguing about what is or isn’t natural has officially lost the debate.

Perhaps the most humbling part is how little we know about them. Their reproduction, lifespan, and population numbers remain mysteries. They’re too deep for casual observation, too fragile for easy study. They hover in that liminal space between myth and reality, known mostly from brief encounters and deep-sea footage. Which, in a way, only adds to their power. They remain alien, unknowable, drifting balloon-shadows in the dark.

So what do we make of the gulper eel? It’s not the fiercest predator, not the most beautiful fish, not even the rarest. But it is unforgettable. It’s a reminder that the universe doesn’t need to leave our planet to create aliens. The deep sea already has them. And this one, with its balloon head, glowing lure, and string-bean body, might be one of the strangest of all.

So next time you’re tempted to call something “unnatural,” remember the gulper eel. Remember the shoelace body, the mouth that unhinges into a nightmare balloon, the glowing tail that lures victims like moths to a lamp. Remember that it’s been doing this quietly for millions of years, unfazed by human disbelief. And maybe, just maybe, remember that being weird is often the best survival strategy of all.