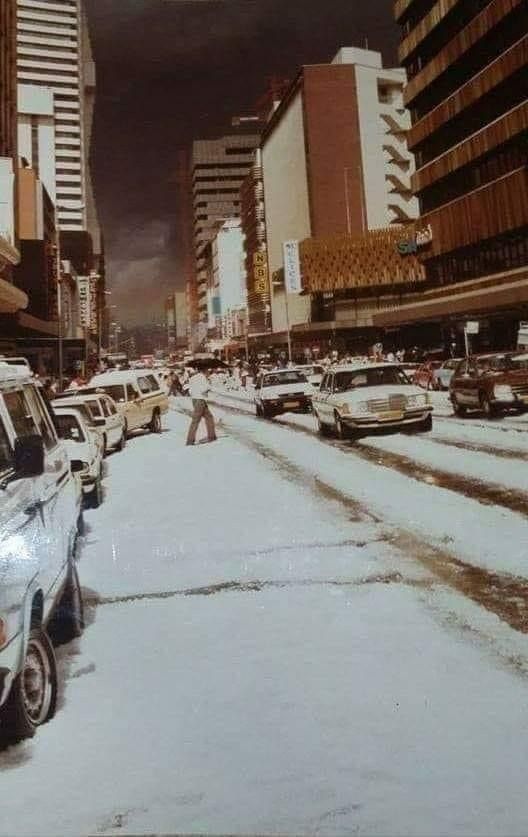

If you want to witness pure South African chaos, forget politics. Forget rugby referees. Just wait for snow in Johannesburg. Because nothing, absolutely nothing, confuses this city more than frozen water falling from the sky. It’s like watching toddlers discover glitter. In July 1981, that’s exactly what happened. For one glorious day, Joburg turned white — not metaphorically, not in the tax bracket sense, but literally blanketed in snow. And the city collectively lost its mind.

Johannesburg is built for extremes, but not that kind. Heatwaves? Sure. Thunderstorms that could scare Thor himself? Every week. But snow? That’s fantasy land. People had only heard their grandparents talk about it — vague tales of a “white winter” in the 1950s that everyone assumed was exaggerated nostalgia. Then, on a cold winter morning in July ’81, the unthinkable happened. Snowflakes started drifting over the skyline, and for once, the city stopped complaining and just stared.

By mid-morning, the highways were silent. Office workers abandoned desks. Schoolchildren poured into the streets in uniforms clearly not designed for alpine conditions. People used braai tongs as snow shovels, saucepan lids as sleds, and dishwashing gloves as “winter wear.” Neighbours who hadn’t spoken in years were suddenly pelting each other with icy clumps like long-lost cousins. There was no time for logic. The entire city became five years old again.

Radio presenters couldn’t believe it either. Traffic reports sounded like wartime broadcasts: “We’ve got heavy snowfall in Randburg, repeat, actual snow, not hail.” Newspapers scrambled to capture the moment. The Star ran photos of children building snowmen outside Hillbrow flats, while one bewildered man in Benoni was interviewed for turning his bakkie into what can only be described as a mobile snowplough. The headline the next day summed it up perfectly: “Snow Joke — It’s Real!”

The city’s infrastructure, however, was less amused. Power lines froze. Water pipes burst. Taxi drivers tried to operate as if physics didn’t exist, which went exactly how you’d imagine. The N1 resembled a slip-and-slide designed by Satan. Sandton’s gardeners discovered that tropical plants are, in fact, mortal. And yet, through all the chaos, people laughed. For one day, Joburg was united — not by politics or sport, but by a shared sense of disbelief.

There’s something magical about that kind of collective awe. It cuts through cynicism like a warm shovel through slush. The same people who’d spent years complaining about potholes were suddenly out photographing icicles on stop signs. Even the city’s notorious impatience softened; horns honked less, strangers smiled more, and someone inevitably tried to braai in the snow. Because of course they did. It’s not a South African event until someone says, “Let’s put wors on the fire.”

And then, just as quickly as it came, it was gone. By late afternoon, the snow had turned to slush. By evening, the city was wet, muddy and back to normal — except for the stories. Every family had one. Every parent would spend the next forty years saying, “You should’ve seen it, real snow in Joburg, I tell you.” And every generation since has waited for it to happen again. It has, sporadically, but never with quite the same drama. 1981 was the year the city forgot its stress and just marvelled.

What makes it so memorable isn’t the rarity of snow — it’s how it made people feel. Johannesburg is a tough city, built on ambition, caffeine and minor traffic rage. Its heart beats fast. It doesn’t stop for anything. But that day, it did. Everyone slowed down, looked up, and grinned like kids who got away with something. The world felt softer. Even the usually suspicious pigeons looked confused, like “we didn’t sign up for this nonsense.”

There’s a photograph from that day that sums it all up — kids building a snowman in Soweto, bundled in mismatched clothes, smiles wide enough to melt the flakes before they landed. That photo made front pages around the world because it said something beyond weather. It showed joy, unity, wonder — things Joburg has always had but doesn’t often show. It was ordinary magic, and for once, we didn’t rush past it.

People still talk about the smell of the air that morning — sharp, clean, and strangely comforting. Old photos show a skyline softened by frost, taxis dusted like pastries, and a city that looked, just for a moment, like it belonged on a Christmas postcard. It didn’t matter that it was July or that half the country had never even seen snow. For those few hours, Johannesburg was enchanted.

The science behind it is simple enough. A perfect collision of cold air masses, moisture, and luck. But explaining it with meteorology feels almost disrespectful. It wasn’t just weather — it was a cultural event. It was proof that even the most unpredictable city can surprise itself. Maybe that’s why the story keeps resurfacing every winter. It’s a reminder that beauty sometimes comes when you least expect it, in forms you don’t prepare for, and disappears before you can figure out what to do with it.

And because this is South Africa, we immediately tried to turn it into something practical. One newspaper suggested “snow tourism.” Another proposed an annual “Winter Festival.” The city council reportedly discussed buying snowploughs — before realising they’d probably gather dust for another forty years. Within a week, the headlines moved on. But the memory stuck like cold fingers to a metal railing.

Ask anyone who was there, and their eyes light up. They’ll tell you where they were, what they wore, who they threw their first snowball at. It’s one of those shared experiences that quietly sits in the national archive of nostalgia — alongside 2010’s vuvuzelas, Y2K panic, and that time the power came back earlier than expected. It’s a reminder that this country, for all its madness, still knows how to be amazed.

Maybe that’s why the story refuses to melt. Every winter, as temperatures drop, someone posts a grainy photo with the caption “Remember 1981?” The comments fill up with people who swear they were there, even if they weren’t. It’s become folklore now, a comforting myth that reminds us we once saw something impossible. And that, for a brief, frozen day, Johannesburg forgot to be cynical.

Because that’s the real story of the snow — not the meteorology, not the damage, not the chaos. It’s how it turned the city soft. How it gave people something to marvel at instead of complain about. How it proved that even in the most concrete of places, wonder can still find a way to fall.