Long before books filled shelves, before films lit up screens, before voices crackled through headphones on podcasts—there was the storyteller.

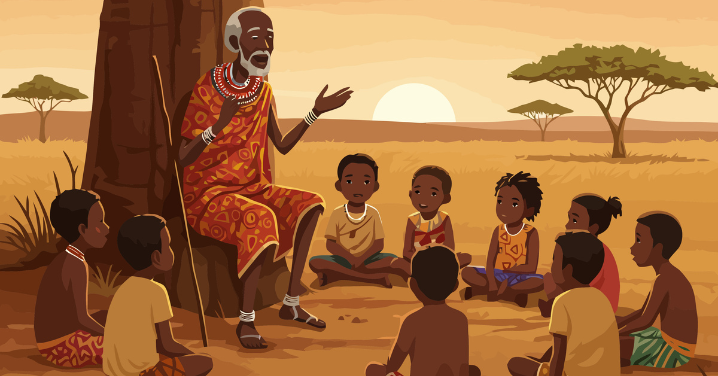

Take a sip of your coffee and let me paint a scene for you, image a fire crackling under a starlit sky, faces bathed in its warm glow, a hush settling over the gathering as someone begins to speak. No script, no slides, just words spun like thread into something far greater: laughter, memory, guidance, identity.

In Indigenous cultures across the globe, storytelling isn’t just entertainment—it’s architecture. It builds culture, binds community, and bridges generations. It is, quite literally, how knowledge survives and how people remember who they are.

The First Libraries Had No Walls

In many Indigenous societies, stories were—and still are—the primary tools of teaching. Long before alphabets, oral tradition served as the encyclopedia, the atlas, the rulebook, and the sacred text.

A tale wasn’t just a tale. It was a lesson in survival: how to read the stars, track the seasons, find water, heal wounds. It was a moral compass disguised as a fox, a mountain, or a mischievous trickster. The stories explained how the world came to be—and how to live well within it.

They’re rich with symbolism. In one culture, a river might be both a literal place and a spiritual journey. In another, a talking animal isn’t just comic relief—it’s a mirror of human nature.

Dreaming the World Into Being

Among the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, storytelling is inseparable from the sacred. Their stories—called the Dreaming or Dreamtime—are not only narratives of creation but living laws. They describe how ancestors shaped the land and how humans must live in balance with it.

But here’s the twist: Dreaming stories aren’t limited to words. They live in song, dance, painting, and ritual. You don’t simply hear a Dreaming story—you feel it. You dance it. You carry it in your footsteps across the land, because the stories are the land.

Winter is for Weaving Worlds

Travel to the snowy landscapes of North America, and you’ll find another rhythm to storytelling. Among the Haudenosaunee, Lakota, and Navajo peoples, winter is storytelling season. It’s when the earth rests and families gather close.

Storytelling here is often the elder’s domain—earned through wisdom, memory, and deep respect. Their tales might stretch across several nights, looping and morphing as they go. There’s no fixed script, because stories are alive. They breathe and grow, just like the people who carry them.

The tone can be rhythmic, humorous, poetic—sometimes all at once. The storyteller isn’t just talking. They’re performing—with gesture, song, and knowing glances that draw the audience in like magic.

The Griots: Keepers of Memory

In West Africa, storytellers are called griots or jalis—and they’re nothing short of human libraries. These oral historians are trained from childhood to memorize entire genealogies, historical events, and epic sagas like the story of Sundiata Keita, the Lion King of Mali.

Their storytelling is a full-body experience—part song, part drama, part sermon. With instruments like the kora (a 21-string harp-lute), griots blend fact with metaphor, history with mythology, always dancing between memory and performance. Their words don’t just preserve history—they make it unforgettable.

Speaking the Ancestors in Aotearoa

In the Māori culture of Aotearoa (New Zealand), storytelling is deeply rooted in whakapapa—genealogy. Every story links the speaker to their ancestors, the land, and the cosmos.

But the beauty doesn’t stop with words. Carvings, tattoos (moko), chants, and songs (waiata) are all storytelling mediums. Oral tradition becomes physical, visual, and musical. It’s not just about what you say—it’s where, how, and why you say it.

Stories of Resistance in South Africa

In South Africa, storytelling has long been a vessel of culture, particularly among the Xhosa, Zulu, and Sotho peoples. Folktales feature clever hares, patient tortoises, or wise elders—characters who sneak powerful messages into bedtime stories.

During apartheid, when expression was policed and silenced, storytelling whispered truth through parable. It kept culture breathing in the shadows. Even now, tales of Ubuntu—humanity toward others—continue to shape the next generation with values of dignity, kindness, and resilience.

Stories as Survival

Across every continent and culture, one truth remains: storytelling is not just for passing time. It’s for passing knowledge. Especially in times of colonisation, forced migration, and cultural erasure, stories have been the invisible threads holding identity together.

When lands are taken and languages banned, stories survive. They are cultural anchors in stormy seas—reminding people not only of where they come from, but who they are.

The Story Continues…

Today, Indigenous storytelling isn’t fading—it’s transforming. You’ll find it in graphic novels, video games, podcasts, stage plays, and animated films. It’s streaming, it’s trending, but it’s still sacred.

Because at its core, Indigenous storytelling remains what it has always been: a gift. A relationship. A living act of remembrance, connection, and purpose.

So next time someone begins with, “Long ago…” or “There once was…”—stop and listen.

You’re not just hearing a story.

You’re being trusted with a legacy.

And that is a rare and powerful thing.