Imagine being an ancient astronomer—well, technically a priest-slash-stargazer-slash-sky-whisperer—looking up at the sky and realising the sun’s just disappeared in the middle of the day. Cue chaos, confusion, goats panicking, villagers thinking the world’s ending, and you trying to keep your cool while frantically flipping through your stone tablets. That was the vibe before we had apps that send us push notifications about eclipses two years in advance. And yet, somehow, despite no Wi-Fi, no telescopes, and certainly no Twitter updates, ancient civilisations actually got pretty good at predicting these celestial vanishing acts.

Take the Babylonians, for example. These folks weren’t just into writing long-winded texts on clay—turns out, they had some serious eclipse street cred. They kept meticulous records of lunar and solar eclipses, spanning centuries. By doing some hardcore pattern recognition (without the aid of Excel, mind you), they identified what’s now known as the Saros cycle—a roughly 18-year, 11-day pattern in which eclipses repeat. They didn’t call it that, obviously. That name came later, probably from someone in a tweed jacket. But the Babylonians had it sussed. Eclipses weren’t just random drama; they were part of a cycle you could track.

Meanwhile, the ancient Chinese had a slightly different approach. They were definitely aware of eclipse cycles, but their predictions came with a solid dose of imperial pressure. Eclipse prediction was seen as a way to prove cosmic order under the emperor’s rule. Get it right, and you were a celestial genius. Get it wrong, and it was possibly the last forecast you’d ever make. There’s even a story about two court astronomers, Hsi and Ho, who failed to predict a solar eclipse—and were reportedly executed for it. So, no pressure, then.

Over in Mesoamerica, the Maya weren’t exactly sitting around waiting for someone else to explain the cosmos either. They combined astronomy with deeply rooted mythology, calculating planetary movements and eclipse seasons with jaw-dropping precision. Their codices (which are basically ancient comic books filled with symbols, deities, and calendar info) included eclipse tables that helped them anticipate when these sky events would occur. The Maya also used a 260-day ritual calendar and a 365-day solar calendar—interlocking gears of timekeeping that would impress even your most organised mate with a bullet journal.

The Greeks eventually got in on the action too. Thanks to thinkers like Hipparchus and later Ptolemy, ancient Greece became a hub for mathematical models of planetary motion. They built theories based on the geocentric model (where everything revolved around Earth, which we now know is wrong, but hey—points for effort). Their calculations weren’t just abstract: eclipses could be anticipated, timed, and mapped, proving that even without modern science, humans were always looking up and trying to make sense of it all.

Even in ancient India, astronomers like Aryabhata and Varahamihira worked on models that could accurately describe lunar and solar eclipses. Rather than seeing eclipses purely as supernatural omens, they approached them with geometry, observation, and a surprising amount of scientific insight for their time. The Surya Siddhanta, a 4th-century astronomical text, describes the size and distances of celestial bodies with eerie accuracy. All this without even a calculator.

And let’s not forget the Egyptians. While they were more into tracking the movements of the sun and Sirius to manage agriculture and rituals, they were aware of eclipses, even if they didn’t predict them with the same precision as the Babylonians or Maya. Still, the sky was a massive deal—tied to gods, kings, crops, and cosmic balance.

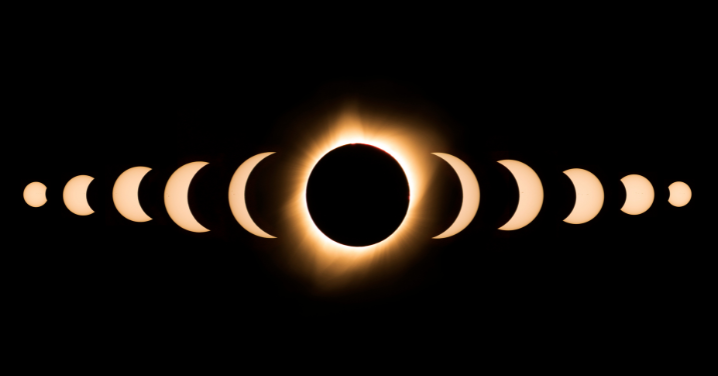

So how did they do it? Well, mostly through observation. Day after day. Year after year. Imagine sitting on a stone bench for decades, just watching the sky and jotting down notes with a stick. Tedious? Probably. Impressive? Hugely. These early astronomers (or sky nerds, as we’d call them now) noticed patterns—the moon takes about 29.5 days to go from full to full, eclipses tend to happen in seasons, and if you see one, there’s a good chance another will follow in about 18 years.

There’s something oddly comforting about that. Despite cultural differences, ancient civilisations all shared one thing: a need to understand the sky. Whether it was to please the gods, guide the harvest, or avoid being executed by your boss, eclipses mattered. They were dramatic, rare, and a little terrifying—like nature’s way of reminding everyone who’s really in charge.

Today, of course, eclipses are still exciting. We just experience them with less goat sacrifice and more eclipse-viewing glasses. But knowing how much effort went into understanding them in the past makes every celestial event feel a bit more special. It’s not just a shadow crossing the sun—it’s part of a legacy of curiosity, of looking up and wondering. And in a world that often has us staring at screens, maybe that’s the kind of perspective we need.